If the only things certain in life are death and taxes, then the only things certain in craft beer are inspectors and taxes. For brewers looking to release a new label, that means working with the once-dreaded Taxman.

Although it can look daunting, the process of label approval through the federal government has become more streamlined in recent years, and the brewers and designers we spoke with agree that once they narrow down some basic rules, receiving approval is relatively painless.

First off, who oversees beer labels? That’s the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, otherwise known as the TTB, which emerged in 2003 with the reorganization of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. The TTB collects taxes, admittedly, but it also serves an important protective function. Its mission, according to their website, is “to protect the consumer of alcohol beverages through compliance programs that are based upon education and enforcement of the industry to ensure an effectively regulated marketplace; and to assist industry members to understand and comply with Federal tax, product, and marketing requirements associated with the commodities we regulate.”

That’s a government-speak way to say that by creating and enforcing specific and enforceable guidelines for things such as beer labels, the TTB is protecting American consumers from possible harm caused by unclear or potentially misleading labels. For example, in order to get a Certificate of Label Approval/Exemption (COLA) to sell beer across state lines, a list of every ingredient in a beer needs to be sent into the TTB.

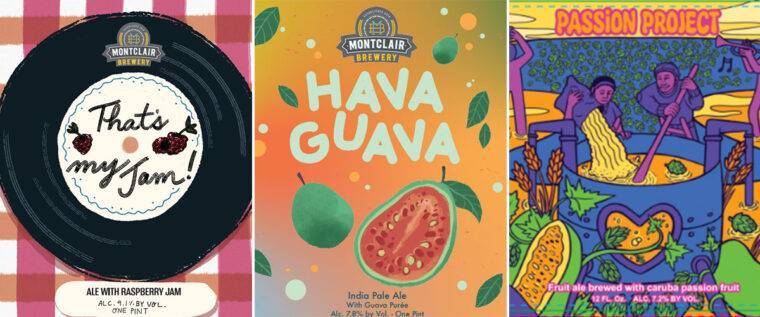

Denise Ford Sawadogo is familiar with this process. As co-owner of Montclair Brewery in New Jersey, she and her husband have several beers that fall outside of the basic “water, malt, hops, yeast” formula allowed in the general COLA list. The TTB requires a form for any malt beverage product “to which fruit, fruit juice, fruit concentrate, herbs, spices, honey, maple syrup, or other food materials” are added.

Montclair’s BaoBiere, a 7.8-percent blonde ale that uses the fruit of the baobab tree, falls into the TTB’s special approval process, as does its Fragile Like a Bomb, a 7.8-percent golden ale infused with baobab and lavender. The baobab fruit, from the tree native to Africa, Madagascar, and Australia, reflected Montclair’s owners’ African-American heritage, but was outside the list of pre-approved ingredients allowed by the TTB. Despite the extra forms required, Ford Sawadogo says the process was still pretty quick, taking only, “maybe two weeks, if memory serves me right.”

Still, it’s not entirely painless. That two weeks was for approval for the formula for Montclair’s beers. Brewers do also have to submit their beer label to the TTB at the same time for approval. This can cause a few trip-ups, says Ford Sawadogo. Figuring out what can and cannot be included on a label, and what must be on the label, can be a challenge, and “there is always some issue—and it is very inconsistent. It probably depends on who reviewed the label,” she says. “Even something that was approved for another beer that wasn’t an issue is now all of a sudden an issue.”

Missy Cooke from Old Nation Brewing Company in Michigan agrees that inconsistency is a problem when it comes to their labels. “Regulations are interpreted differently by different TTB employees, regulations change, and sometimes things are approved that technically didn’t follow a certain rule,” she says. “In theory, if it works once, it will work again—but not always.” In her experience, even if a label looks identical to one that has been approved before, “the TTB doesn’t look at approved labels as having set some sort of precedent.” On the FAQ section of its website, the TTB provides a list of allowable changes to an approved label, which includes deleting non-mandatory information or artwork, deleting or changing an optional barrel age statement, or changing award statements or brewers’ signatures.

That makes sense, since the TTB has more than one agent on the approvals team. That wasn’t always the case: until his retirement in 2015, the aptly nicknamed Kent “Battle” Martin was the sole person in charge of label approval at the TTB. Dubbed the “beer bottle dictator“ by The Daily Beast, Martin reviewed tens of thousands of label applications a year, and was known to deny applications for nitpicky, even pedantic, reasons. Nowadays, the department in charge of COLA applications has several employees, so there is no guarantee that nearly identical labels by the same brewer will all get approved.

As the creative director and partner of CODO Design, a graphic design firm that designs dozens of craft beer labels, Cody Fague has a few pointers for new and seasoned brewers. First, he says, eliminate abbreviations. IPA for “India pale ale” will be universally rejected, as will ABV for “alcohol by volume.” When in doubt, spell it out, he says, “even if everyone on the planet knows what an IPA is by now.” Details such as these are the “ticky tacky stuff” that Fague and his partners help their clients navigate.

“As a consumer protection body, they’re more interested in making sure that none of your advertising copy on the packages suggests that it’s going to have any kind of physical or pharmaceutical effects,” says Fague of the TTB. He was once rejected for a label on an English strong ale because a TTB agent didn’t like the word “strong” and thought it implied that the beer would make drinkers physically strong.

The TTB can get its hackles up with use of any claims to health benefits. In its FAQ statements, the agency notes that the word “clean” on a malt beverage product might “create the misleading impression that consumption of the alcohol beverage will have health benefits, or that the health risks otherwise associated with alcohol consumption will be mitigated…We would consider those claims to be misleading health-related statements.” While the word “clean” isn’t expressly forbidden, Fague notes that it’s probably wisest to avoid any claims that imply that alcohol is good for the consumer.

That said, and taking all these concepts into consideration, Fague says that “at the federal level, they’re not going to get into illustration style or colors.”

Once a beer gets to the state level, that might go out the window. In New Hampshire, some consumers are lobbying for new restrictions on cartoon characters on beer labels. The law would prohibit the depiction of toys, robots, cartoons, and fictional animals or creatures on adult beverage labels. While it’s unclear whether existing labels with these depictions would be required to change, in some cases, breweries have agreed to change their labels (e.g. Concord Craft changed its Finding NEIPA label, which depicted cartoon fish similar to those in the movie “Finding Nemo,” after talking with the state of New Hampshire). While he understands that the COLA process is in place to protect minors, Fague is keeping a close eye on the situation there.

Joe Harer from Other Half Brewing distributes beer throughout the Northeast and hasn’t had too much difficulty at the state level. “The TTB is the end-all-be-all,” he says, and “once the TTB approves something, the states will accept it.” The TTB restrictions certainly didn’t stop him from going for broke a couple of years ago when he submitted a label design for a triple IPA—er, India pale ale—made with Galaxy hops called Space Hallucination. Harer received a quick but firm “no” from the TTB agent in charge of his COLA. “I tried explaining to the person checking the label that you can hallucinate without drugs,” he says, “but they didn’t like that very much.”

Despite the occasional setback, everyone we talked with agreed that the process has become quite efficient and speedy, especially in the last year or so. Says Harer, “As of the past year or two, they’ve been very, very much on the money.” In the past, his labels have taken a few weeks to be approved or denied. Now, he’s seeing a turnaround of just a few days’ time.

Brewers recommend reading the COLA requirements carefully before submitting an application. They also suggest saving your energy and to not bother arguing with TTB agents over what is and isn’t acceptable. “Getting caught up in the disparity of whether or not a new label is approved slows down the whole process because it doesn’t matter,” says Old Nation’s Cooke. “The quickest way to approval is to just accept what they’re saying, make the changes as quickly as possible, and resubmit.” This is still the federal government we’re dealing with, after all.

The post Beer Label Bottlenecks appeared first on CraftBeer.com.